Issue no. 2

I'm glad you're back for more. Let's get into it.

This is not the first time I’m alone, with lamentably low phone battery, in an airport in a country where I don’t speak the language and I look different from everybody around me in an immediately noticeable way. I used to panic like crazy when this happened - a metallic, paralyzing kind of fear - but now, standing just outside of the airport in Mexico City, waving away unlicensed cabs and too-curious old men as I use my last 4% batter to plan a meet-up with my friend I am observing how what I once knew to be an all-consuming fear as just a distant siren of panic going off somewhere in the far reaches of my brain no louder than the buzzing of a gnat near your ear.

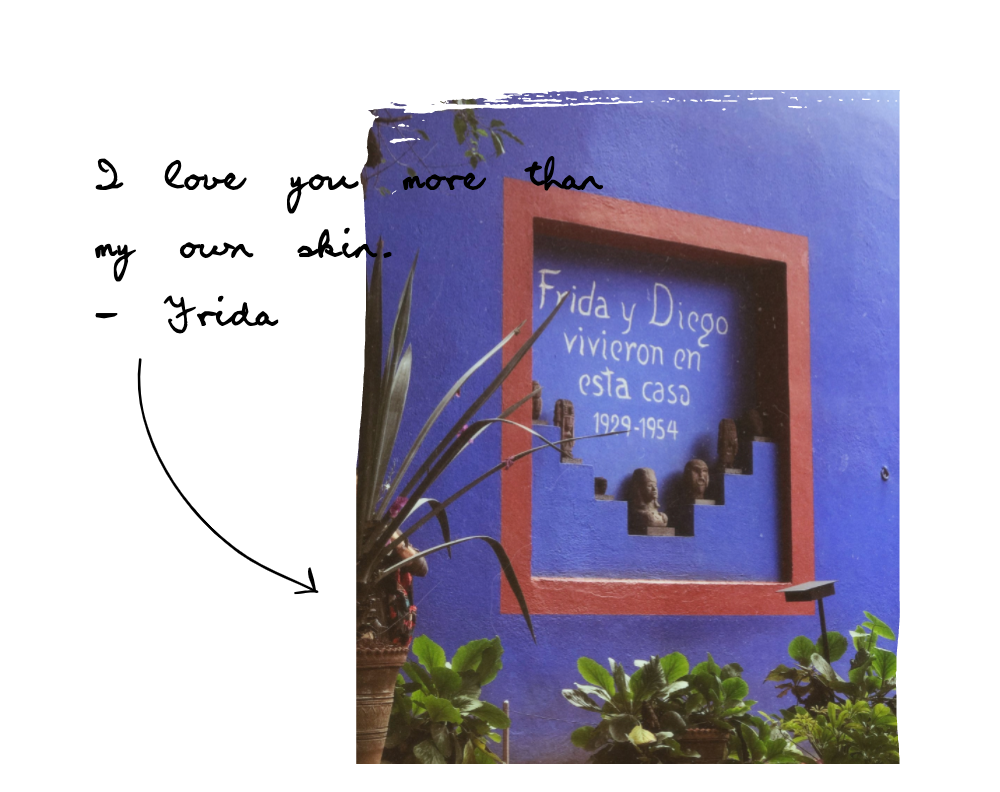

The first time I knew real fear on my trip to Mexico wasn't during a late night walk on an unlit street or in the backseat of a car with a reckless driver - it was in a garden bursting with flowers on a sunny day in a serene blue house in Coyoácan. The place where Frida Khalo entered and exited the world, with love and pain and art in between. Once I got beyond the front room full of paintings I was met with this sinking sadness - signs of their happiness were everywhere - “Frida y Diego” painted on the walls. photos of them when they'd been happy. Here's the pond where Frida likes to come feed the ducks. Here's the bench where Diego liked to read the paper. This is the expansive garden she ran through as a child, took early evening walks with the love of her life, laughing without feeling the time pass, maybe momentarily forgetting the body braces, the ongoing physical pain, this is perhaps where she came to process the discovery of his affair with her sister, here's where she plotted her revenge. It could be a beautiful story if I didn't know how it ended: Frida and Diego had a deep, intense, creatively fulfilling, selfish, all-consuming, destructive, life-ruining kind of love that I felt the distant but still crushing weight of echoing off the smooth cobalt blue walls.

When Frida's body surrendered to its excruciating fragility at just 47, after she and Diego had remarried in the ashes of their first marriage, scorched and battered from a trail of infidelities and other ugliness. Even after everything, they'd believed they could start fresh, with eachother, being the only people they believed could fully understand and fulfill eachother. Its a bizarre kind of loyalty that's difficult to understand, yet millions of people continue to search the corners of their love story in books, movies, letters, on the walls here. It was Diego who once said “If I ever loved a woman, the more I loved her, the more I wanted to hurt her. Frida was only the most obvious victim of this disgusting trait" and it was Diego who ultimately turned this home into a museum to honor her and them - a time capsule of when they'd been happy.

Why, if we know how ugly the ending was, are we obsessed with this story? I think its because we all hope for love and intimacy so deep and intense that it could have the power to destroy us, but with faith and hope that our loved ones will never use their power to hurt us. To love and allow ourselves to be loved and seen this deeply is one of life's biggest and most dangerous risks. But I'm sure you already know what they say about risks and rewards.

When I was a child in what I think were actually supposed to be my most intrepid years I was afraid of everything - strangers, water, the dark, thunder, staying out late, long silences, being called on in class, not being called on in class - and being embarrassed by small stupid meaningless things like walking into class with toilet paper stuck to my shoe or being called something lame like “2000 and late” by some popular girl in what I now know to be truly hideous makeup and attire. I didn’t know true fear. I was lucky enough in my youth that I was protected enough to have trouble couldn't even begin to conceptualize what real fear is. The kind of fear that most of the world is forced to deal with young without censorship or sugarcoating - the fear it takes to outrun poverty, famine, or illness, fear of being directionless, the fear that comes with learning to trust and love again after rubbing up against heartbreak and dishonesty, the growing understanding of mortality that comes with each of your parent’s new gray hairs, being forced to leave your home, looking into the face of everyone you meet and understanding that none of us are long for here, the fear that maybe, despite the grand expanse of your imagination you’re just meant to lead mediocre, predictable after all, the fear of becoming someone you used to be. That's real fear.

The fear I recognized in Frida and Diego's home came from the clear understanding that in life we cannot avoid running into pain if we ever hope to run into love. Fear and love are the closest of companions. Life can be beautiful, but you will never avoid pain if you hope to live fully. Maybe in your life, you will never experience the depth of pain that Frida and Diego put eachother through. Maybe you will never have the kind of hurt that she carried with her for years after her accident. But there has to be a moment of clarity where you understand that to live fully you cannot avoid, on some level, hurting and being hurt by the ones you love - but this does not under any circumstances mean that you should ever stop loving.

I no longer wish to be fearless. The human animal is made to feel things. We need our fear. The goal is mastery of it. We need to learn the textures of fear to understand when it’s telling us a situation is a hostile environment or how hard we are willing to fight for the things we want or to know just how deeply we love something.